The logo of U.S. conglomerate General Electric is pictured at the site of the company’s energy branch in Belfort, France, February 5, 2019. REUTERS/Vincent Kessler/File Photo

Analysis: Banks profit from building up and breaking up companies

Nov 16 (Reuters) – It is a constant dilemma facing companies; do they acquire or shed businesses to boost shareholder returns? Investment bankers profit every time the answer involves a deal, even if it represents an about-face for the companies.

Last week’s announcements by General Electric Co (GE.N), Toshiba Corp (6502.T) and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ.N) of their plans to break up offer the latest examples of how some companies have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on investment banking fees to bulk up through acquisitions over the years, only to pay more fees to reverse them.

Some of the banks that worked on preparing these spin-offs – Goldman Sachs Group Inc (GS.N), JPMorgan Chase & Co (JPM.N) and UBS Group AG (UBSG.S) – advised on previous acquisitions that took the companies in an opposite strategic direction.

Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan and UBS did not respond to requests for comment.

Corporate break-ups are on the rise amid a growing consensus on Wall Street that companies perform best only if they are focused on adjacent business areas, as well as increasing pressure from activist hedge funds pushing them in that direction.

Some 42 spin-offs collectively worth over $200 billion have been announced globally so far this year, up from 38 spin-offs worth roughly $90 billion in 2020, according to Dealogic.

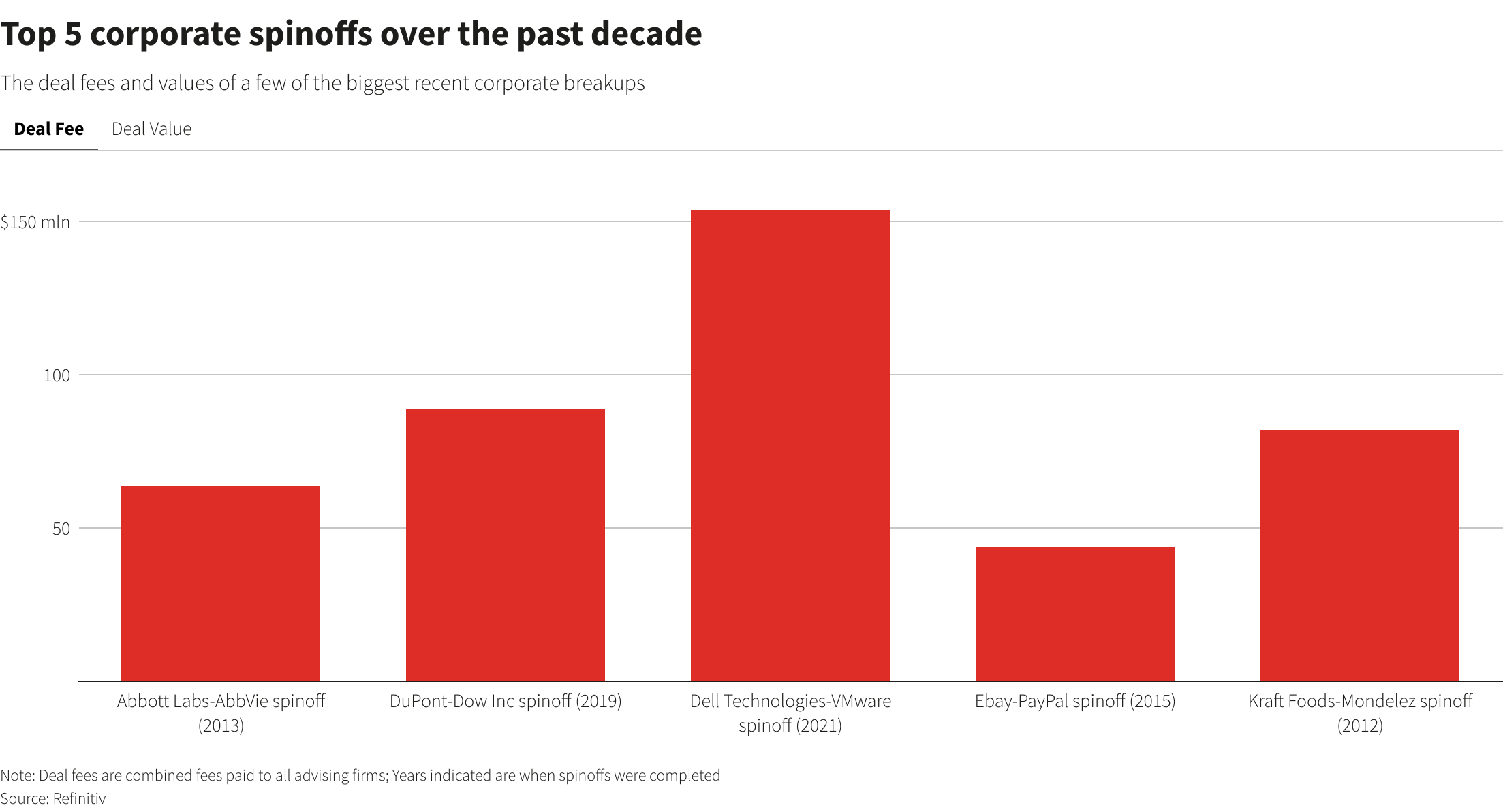

Investment banks have collected more than $4.5 billion since 2011 advising on spin-off deals globally, according to Dealogic. While this represents less than 2% of what they pocketed from deal fees overall, it is a growing franchise; banks have so far earned over $1 billion on spin-offs globally so far this year, nearly twice what they earned in 2020, according to Refinitiv.

For an interactive graphic, click on this link: https://tmsnrt.rs/3cgKJ9M

In the case of GE, financial advisors including Evercore Inc (EVR.N), PJT Partners Inc (PJT.N), Bank of America Corp (BAC.N) and Goldman Sachs each stand to collect tens of millions of dollars from their advisory roles on the company’s break-up, according to estimates from M&A lawyers and bankers.

Goldman Sachs had previously collected nearly $400 million in fees advising the company on acquisitions, divestitures and spin-offs over the years, making it GE’s top advisor based on fees collected, according to Refinitiv.

Industrywide, Goldman Sachs has earned the most in fees from advising on corporate break-ups thus far in 2021, followed by JPMorgan and Lazard Ltd (LAZ.N), according to Dealogic.

Yet while investment banking fees are secure, the outcome of dealmaking for a company’s shareholders is far from certain. Shares of companies that engaged in acquisitions or divestments have had a mixed track record, often underperforming peers in the last two years, according to Refinitiv.

INDEPENDENT ADVICE

To be sure, investment bankers argue that some combinations do not make sense for ever. Changes in a company’s technological and competitive landscape or in the attitude of its shareholders can push it to change course.

For example, GE shareholders were initially supportive of its empire-building acquisitions in businesses as diverse as healthcare, credit cards and entertainment, viewing them as diversifying its earnings stream. When some of these businesses started to underperform and GE’s valuation suffered, investors lost faith in the company’s ability to run disparate businesses.

Bankers often also argue that most companies want to pay bankers for delivering deals rather than advice on whether they need to do a deal in the first place. This creates incentives for bankers to try to clinch a transaction rather then the best outcome for their client that may not involve a deal.

It also offers ammunition to Wall Street critics who argue that companies cannot rely on banks for independent advice on whether they should pursue a deal.

“Companies should develop valuations in-house and with help from unbiased third-party advisers, whether or not they also hire an investment bank,” said Nuno Fernandes, professor of finance at IESE Business School.Reporting by Anirban Sen in Bengaluru and David French in New York; Editing by Greg Roumeliotis and Stephen Coates

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

This article was originally published by Reuters.